TAMING THE RIVER GOD – DIVING THE KARIBA DAM

© Ian Robertson, 2006

The Zambezi

In high flood, the brown waters of the mighty Zambezi River tumble over the brink and plunge 100 m into a mist-filled zig-zag chasm. The air over the falls is obscured with spray and the bright African sunlight is split into rainbow colours. Both the air and the ground quiver with the force of cascading water. This is the ‘Smoke that Thunders’, discovered by intrepid explorer, Dr David Livingstone, in 1855, and named the Victoria Falls.

The Zambezi plunges over the Victoria Falls: The Smoke that Thunders. Photo David Trickett.

The completed Kariba Dam with all six floodgates open. Erosion of the dams foundations was inevitable.

Some 100 km down stream, the turbid waters of the Zambezi leave the gorge and flow gently through a broad valley occupied by a peaceful people, the Batonka. Some 250 km further down stream, the river joins with the Sanyati River and enters the Kariba Gorge, where the river is confined by narrow, rocky banks and the speed of the water picks up. The entrance is guarded by a massive rocky outcrop, said by the Batonka tribesmen to be Mnyaminyami, their Zambezi River God.

The Kariba Dam

This forceful flow of water has impressed many since Livingstone. Its flow was first measured in 1914 and, in 1938, it was first considered as a hydro-electric project. From then on, it was only a matter of time before a massive double convex concrete arch dam, 131 m high and 633 m wide, was built and hydro-electricity flowed in plenty. This was a huge undertaking, involving the co-operation of many nations, diverse companies and financial institutions. The first concrete was poured in November 1956. As it was built, Mnyaminyami began to show his displeasure.

Figure 2. The mighty Zambezi overtops the coffer-dam during early construction in March 1958. Nyaminyami is displeased.

Much ingenuity was needed to divert this powerful river and prevent it from destroying the puny efforts to construct the Kariba dam. An unprecedented flood, peaking in March 1958, overtopped much of the construction and Mnyaminyami hurled 16 000 tons of water per second down the gorge. The Batonka tribesmen smiled knowingly. Although the works held, the cleanup was massive. On 20th February 1959 a platform in a shaft to the power station collapsed, hurling 17 workers down 70 m, followed by 200 tons of wet concrete. Gradually Mnyaminyami’s dissatisfaction turned to grumbles as the dam was completed in June 1959 and the huge lake of 3900 km2 began to fill. This happened far quicker than expected. Operation Noah was mounted to save some 6000 animals stranded on shrinking islands as the lake filled.

Dennis Hanson helps me up the ramp of the Gemini in Siavonga harbour after a dive. Photo Christine Miles.

My first dives in Lake Kariba were in January 1960, while the lake filled. The water was warm (27ºC) and murky (vis less than a metre) obstructed by drowned mopane trees. We practiced roped diving and sweep searches. A sharp thermoclyne at 13 m and entry into cold, dark but much clearer water beneath was spooky to a schoolboy.

Early Commercial Diving

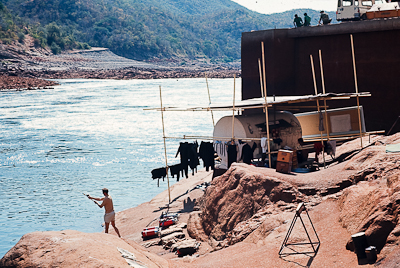

Huge concrete mooring blocks were installed in the planned harbours but these were flooded before anchor chains and buoys could be made and fitted. We were asked, in July 1962, to locate these blocks and connect the mooring buoys and chains at Siavonga and Sengwe harbours. Visibility was generally 2-2.5 m but the water was warm (23ºC). We worked off the Gemini, a flat-topped, twin-hulled barge with a wooden ramp, built for transporting earth-moving equipment. The work involved locating the blocks in 3-5 m of water with sweep searches, moving the heavy chains, weighing 15 kg per metre, and bolting them to the buoys and blocks. The best way to move the chains was to attach them to 200 litre drums with hooks of steel reinforcing rod and float the lengths of chain into place. One air-filled drum could support 12 m of chain. Dropping the chains was tricky and dangerous. We cut through the hooks with a large bolt-cutter, taking care not to get under the falling chain or above the drum that was often dragged under water by the sheer weight of chain. As the steel hook parted, the falling chain left a cloud of rust in the water and the big drum leapt metres in the air. At one point, two ends of a length of chain, piled on the deck of the Gemini, began to run uncontrollably into the water. The final loop of chain rushed towards a group of the crew, lounging on the deck. The whole group seemed to rise in the air, still in a sitting position, as the chain passed under them. This was followed by nervous laughter; it could have been very different - Mnyaminyami again. After two weekends of work, the task was successfully completed.

The Kariba Dam provided plenty of work for a new group of professional divers led by Conrad Wilson (the man who taught me to dive). At one point they emplaced a 17 ton bulkhead in a flooded water intake tunnel, allowing the tunnel to be pumped dry and repaired. This pioneering work was accomplished by diving and lowering equipment down a flooded shaft that narrowed to a metre at one point and working at 39 m.

Initially a huge underground power station was built in the south bank, generating 600 Mw of electricity. Another power station was planned for the north bank but this was not built initially, due to reluctance of the newly independent Zambia to cooperate with Southern Rhodesia. Thus, it was necessary to open all six huge floodgates during peak river flow rather than four, as originally planned. This thundering flow of excess water, some 9500 tons per second, eroded soft mica schist seams beneath the stilling pool below the dam. This left huge underwater caverns in the dams foundations, that needed repair. Long, twisted steel rods, as thick as a wrist, were drilled through the roof of the caverns into their floors. The caverns were filled with boulders and pipes were emplaced through which grouting concrete was forced to cement the whole mass together.

After the next flood, divers inspected the repairs over about a week in 1968 to see how they had held up. The force of the water had again done significant damage. I was a recompression chamber operator for the diving team and had an opportunity to inspect the underwater damage in ‘1220 Cavern’ and ‘Lower Cavern Extension’ for myself with one of the engineers. The light was poor at 30 m and the visibility about 8 m. Cornish jack and huge vundu (catfish) almost 2 m in length patrolled the waters. Rocks, the size of small cottages, lay tumbled about. Huge volumes of the boulders and grout had been stripped away and the steel rods had been exposed and bent into S shapes; Mnyaminyami’s toys perhaps.

Conrad Wilson and his professional diving team on the dam. Masks were different then. Photo Rhodesia Herald.

The stilling-pool was an area of calm with the floodgates firmly closed, but a short way down stream, water from the power station rushed downstream from the tail-races. A few people were fishing to no avail for some abnormally large (5 kg) tiger-fish that were swimming in the relatively calm waters adjacent to the tail-races. The tiger-fish were fattened by scraps of fish that had been drawn into the huge turbines and ejected from the tail-races. They far preferred this feast and ignored the puny bait offered by the fishermen. One of the divers, Fraser Glendinning, took a spear-gun to them. He got too close to the tail-race and was slammed by a wall of water that stripped him of his spear-gun, mask and fins, tumbled him end over end - he was lucky to survive. Fraser was well-tanned but this fright left him grey with shock. Mnyaminyami chuckled.

As the earths crust was loaded with 185 billion tons of water in the lake, small seismic shocks peaked in 1973, as the rocks beneath the lake adjusted. This huge lake has provided a steady supply of electric power for over 46 years, a thriving fishing industry for the Batonka tribesmen, a unique and rich ecology of animal- and bird-life along its shores and many tourist opportunities. We hope Mnyaminyami is at least appeased.

Attempted Gun Recovery - the last laugh

In late October 1969, a young army officer approached our club with the request for a salvage job. Apparently, on returning from a military exercise on the lake, a group of troopies had overloaded an aluminium dinghy, managed to capsize it and had lost some expensive gear, including a machine gun and seven FN rifles as well as the dinghy. They were rather sheepish about this and recovery was clearly important to them.‘Do you know exactly where it happened?’ ‘Oh yes, exactly!’ ‘How deep?’ ‘Probably quite shallow.’ ‘Were we interested?’ ‘Of course!’ Half a dozen of us were bundled into an Air Force DC3, together with assorted dive equipment and a compressor, and flown to Binga, a village on the southern shore of Lake Kariba.

Out on the lake, we took each of the witnesses separately and had them drop a small marker. Here, they were not nearly so sure where it had happened, as there was about 200 m between the markers. We’d give it a go but much would depend on conditions.

Mike Clark and I dropped into warm water (30ºC on the surface) with visibility at 3-5 m. Behind us, trailed the surface-fed cables for the powerful Cessna landing lights and underwater communication cable we were using. Very quickly (at 10 m) we slipped below the bath-warm layer into cooler, murky brown water (25ºC). Suddenly, at 25 m, TREES!! These were trees that had been drowned as the lake had rapidly flooded. The bark had rotted away, leaving the wood still hard and strong, and the branches were coated in a thin layer of silt. Quickly, the light cables became entangled in the branches so we had to abandon them and continue on our way with torches.

At about 30 m, the water temperature dropped again sharply to about 23ºC but, below this, the visibility improved markedly to over 15 m. This was probably anoxic water, as there were no fish. Looking up, we could see the tree branches above us, silhouetted against the cloudy brown water, like in an English wood on a misty winters day! We sank further, past 35 m, but still no bottom. Finally we could see a muddy floor with a few boulders at 49 m. The torch beam vanished into the blackness, revealing mud and more mud. After a quick look around, we could see the task was hopeless. Searching an area bigger than a cricket pitch at this depth, with severe obstructions, was a huge task, would take a long time and was just too dangerous. So… up we came.

After a suitable surface interval and lunch, we spent the next dive untangling our gear from the trees, reaching a maximum of 40 m in doing so. During this, the army managed to capsize another dinghy but nothing of value was lost this time.

Success in search-and-recovery work depends on conditions but it depends even more on being dropped in the right spot! Poor seamanship is probably the norm in the army, which is why there are navies. The weapons and the dinghy are, undoubtedly, still there, in the cold, deep, dark bosom of Lake Kariba, jealously guarded by the spirit of Mnyamenyame, the Zambezi river God of the Batonka who is, no doubt, still laughing.